Growing up in peacetime¶

There were no more raids now, and I hoped that my third baby would be born in peacetime. One morning in early April we thought the war was over, for the flags were flying from houses all up the village street and there were groups of chattering people everywhere. “Is it over?” I asked and was very soon told that the war had not ended yet but that one of the young men of the village who had spent over four years as a prisoner of war had been released from one of the German Prisoner of War camps by the advancing Allies and was nearing home now. His mother was weeping as she led the rest of his family with several of the parish council members round to the station to welcome home the first of the returning prisoners. It was a wonderful homecoming for him but there was a pathos about it that brought a lump to the throat for although he had gone away a strong young eager soldier, he came back thin from years of near starvation and prematurely old.

Peace came to our land in early May and there were great celebrations in the village. A bonfire was lit that evening and an effigy of Hitler was burned to the sound of great cheers. A grand open air party was held for the children and our boys were invited and very proud to sit with the bigger boys at tea.

The day after the party was the day arranged for me to take the boys to Greenhithe, the residential nursery where they were to stay until after the baby was born. I went down to Tunbridge to a very nice village called Langton Green, to await my baby while resting in the wonderful May sunshine in the gardens. We, the other mothers and myself, stayed in a lovely house called “Pavies”. The owner, who with his wife looked after us, had a lovely garden in which he grew fruit (lots of it) on espalier trees and he proudly showed them to us. When the time came for us to be confined we moved to another larger house, now a wartime maternity home called “Northfields”, where our first lovely daughter Anne was born. A couple of weeks later I collected the boys from Greenhithe and took them (all three) to Leytonstone to start life without bombs and gunfire, in our own home.

Joe was demobbed in 1946 in time for our second daughter Margaret to be born, and arranged to come to the Salvation Army Hospital in Clapton in East London to collect us - it was almost Christmas. Before he came on the morning I was due to leave I had a very moving experience. The Salvationist Nursing Sister almost danced into the ward with two of the Salvation Army nurses and announced that baby Margaret was going home today and we must have a little thanksgiving for her. She lifted Margaret, (already in a pretty gown) and on her open hands lifted her up and offered her to God. They all three sang a lovely prayer and then thanked God for this lovely baby and Margaretユs joyful young mother, now well again after her travail. Then they prayed for all of us as a family. It was just wonderful! Joe came and we phoned for a taxi but like all other luxuries they were hard to come by and we were not successful and we had to come home by bus. I was so thankful Joe was there to help me. It meant a change of buses at “Bakers Arms” and a fair walk after we got off the bus. A cold homecoming in a snowstorm for a tiny baby.

Joe started back to work at his old firm “John Wright” after Christmas and the firm was just entering a very busy period rebuilding the business after loss of wartime contracts. He was working overtime as often as possible in order to have enough money for living expenses and to make things easier for me. Washing machines were being advertised and had certainly come into our future plans.

|

Something interesting over there?

After Margaret was born it seemed to take me quite a long time to get back to normal. I was always very tired for there was always a great deal to do and not enough time for me to rest as I should. The overtime meant that Joe was not home early enough to help me with the children’s bath time, and the task of getting them all to bed was no easy one. Once they were tucked up there was a great shambles in the kitchen to be cleared up: piles of small, dirty clothes and the bath water and then the general tidying up of the room.

When Joe came in from work we would always go up to see them in bed and often they were fast asleep. Beautifully clean, with a soft flush on their faces and fast asleep, they looked angelic and made me feel a bit of a monster that I had scolded them during the day. We would watch them for a few minutes and then go down for our evening meal and a little chat over the happenings of the day and it was very nice to have a little while alone without the children around.

Paul started to go to school after Christmas that year and looking back afterwards I realized that it was a rather foolish thing to do, to start him then instead of waiting until the Spring, but the thing that decided me was that he was so eager to learn and anxious to go to school. It proved quite a task this going to school in the mornings, for I had to take all four children out with me. There was no one with whom I could leave them, and in order for him to arrive at nine o’clock, we had to leave the house at about twenty five to nine. It was never any trouble to get the children up, for they were always out of bed and running about long before I was ready for them and able to drag myself from the cosy comfort of my warm bed.

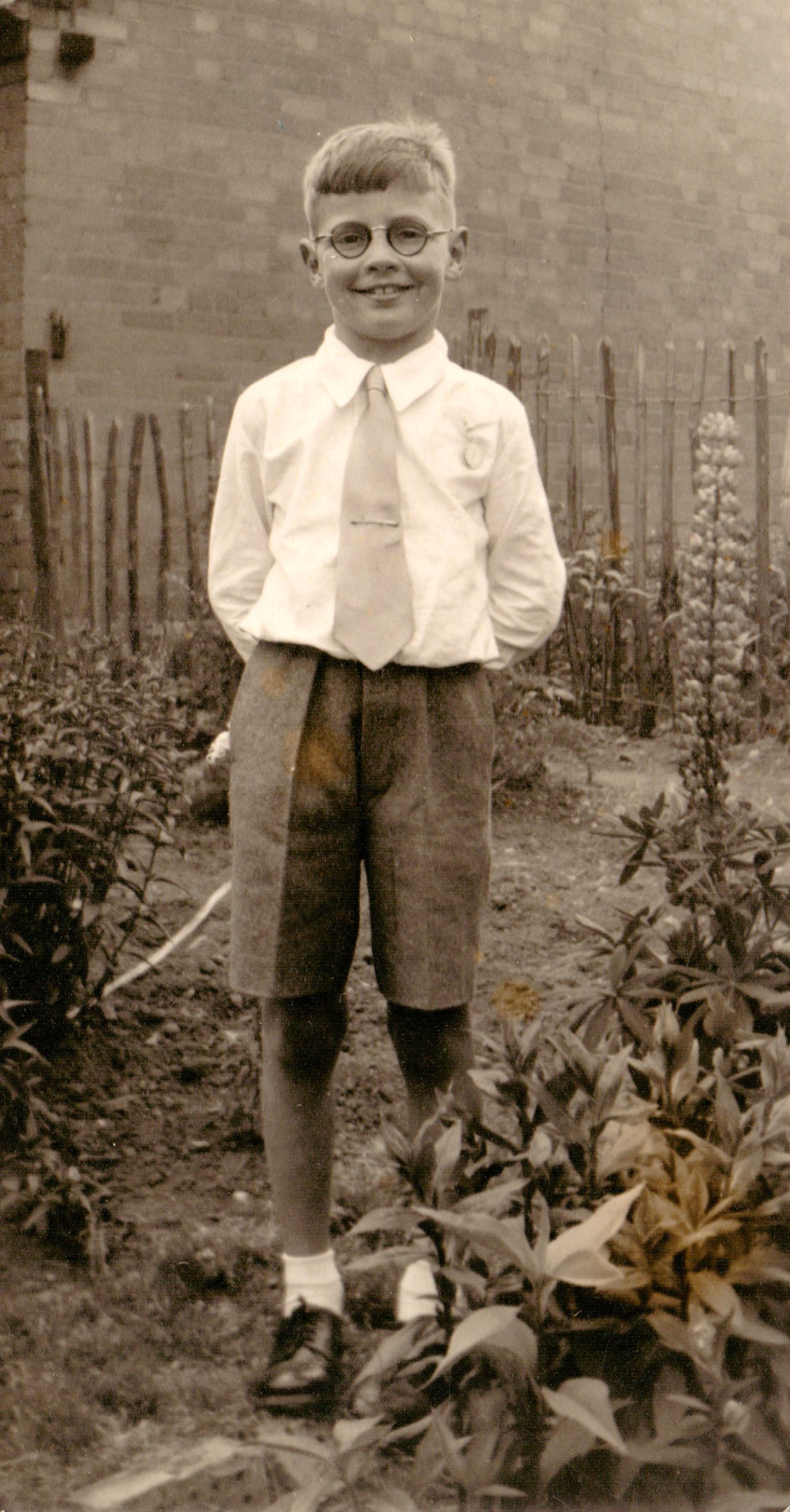

We would have our breakfast in the warm kitchen and I would wash them in there too and get them ready to face the bitter cold outside. I would wrap the baby and Anne up warmly and tuck them in together under the hood of the pram and John would ride on the handle end. Paul, the big schoolboy of almost five years old, would run alongside with his small satchel, containing a snack or sandwich for break time, bouncing on his hip. He was an intelligent little boy but he was very shy and found it quite difficult to get friendly with the other children, but he got great satisfaction from taking some small treasure or novelty to school with him and would carry them backwards and forwards with him every day.

We would leave him at school and then do the shopping for the day; things were still rationed, and the buying of meals required a good deal of thought. We usually ended up with something that I could casserole, for it meant that I would put the oven on and bake the whole dinner in it and having the gas alight in the oven would warm the scullery. Then the children could run from one room to the other and play in both rooms, for the weather was usually too cold to let them go out into the garden - it was to be the worst winter in living memory and had started off with the odd snow storm in November. They could have plenty of fun together with their toys and John and Anne got on very well together and enjoyed the toys that Joe had made for them. There had been no toys in the shops for some years now, but Joe had made them a few pull-along toys and some building blocks, and I had made them several woolly balls with the oddments of wool. These they delighted to throw at each other and would shriek happily if they scored a goal, which meant that they had managed to throw the ball straight enough to hit the other one with it. I played with the children indoors a good deal, for we did not stay out longer than we needed to for those few months, and they both learnt to scribble with a pencil and paper and spent many happy hours with a few crayons and an odd roll of lining paper.

Coal was terribly scarce at this time and it meant that I could only have a very small fire. The rest of the house seemed to be perishingly cold and I wore a coat nearly all the time in the house for I felt the cold badly. There were mountains of dirty clothes to be laundered each day with two babies in napkins and John at the stage when the coal scuttle seemed to have a magnetic attraction for him. I did all this washing in a small galvanised bath tub, in which the children were also bathed. Joe had made a stand for me to bring the tub to the right height in order that I should not have to stoop too much. During that winter I was often glad to get my hands into the tub full of suds in order to warm them up, for the cold was dreadful and there was always the haunting fear of being unable to eke out the coal for the required time. If one used up the ration too quickly there was no help for you, for there was no black market for coal that I had ever heard of, and no way of supplementing the ration except the odd bag of logs that were sometimes sold round the doors, but these burned far too quickly and never seemed good value for money.

I would collect the shopping after taking Paul to school and then we would go home and have a hot drink and the children would play whilst I prepared the dinner. We had a hot meal each day and I would save some of the casserole for Joe and a small dinner for Paul when he came home from school. There were plenty of vegetables and, although it was severely rationed, I always had enough meat; for I had six rations of meat and none of us were, or for that matter even now are, not big meat eaters but we all like plenty of good gravy and nicely cooked vegetables. Fruit was scarce that year and was expensive both in points and cash. Tinned fruit was a luxury very hard to come by and seldom seen in the shops.

With a young family like ours, there were some very great advantages, and the best one of all was that we always had lots of milk, usually about five pints a day and I’m sure that some of my neighbours felt at times that the milkman and me were more than just good friends for they were very envious of my supplies. It meant that we always had a very big milk pudding for dinner and enough left over for hot drinks all round at night and still leave all that the babies needed.

|

|

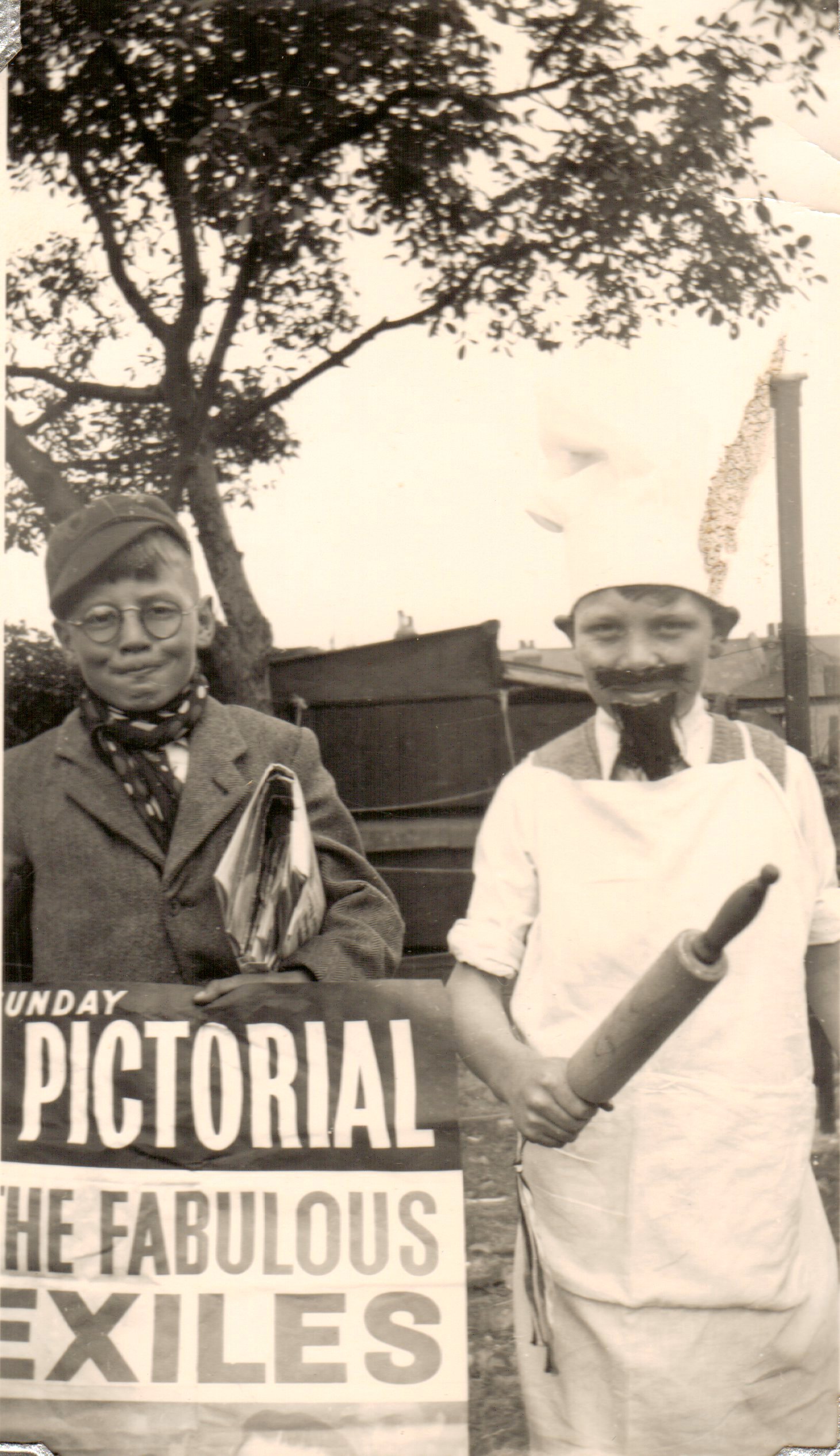

A mischevious lot

Another great help was the free issue of orange juice and cod liver oil, lots of mothers did not even bother to collect these vitamins for their children but ours had always been given the full dose of oil each day and did not blink an eyelid as I poured it down their throats from the spoon. They always had this given when they were in the tub at night and there was no danger then of it getting on their clothes for I knew from what I had heard from other women how hard it was to remove from clothing for the smell would linger for weeks.

The children all loved the orange juice and had the full allowance. John was quite big by this time but he loved me to pour his juice into an empty orange juice bottle and put on the screw cap and then equip him with a straw and then he would go and sit on the stairs and settle himself comfortably, unscrew the cap and insert the straw and drink noisily till it was all gone.

Anne could manage hers quite easily from an orange juice bottle with a teat on the end which left me free to do my chores and to see to the baby. We thought the snow would never go; we began to get worried about the coal situation and with our four young children we dare not let the fire out for one or other of us often had to rise in the wee small hours for a drink or a feed for one of the four and the only solution was to stick rigidly to the one small room and keep that really warm day and night and not bother about the rest of the house.

I suffered a great deal that winter for my legs seemed to ache permanently and it was even difficult for me to get to sleep in spite of my great weariness for the whole of my legs from feet to thighs seemed to throb. We discovered several years later that this was due to the stone floor of the scullery which was only covered with a thin, cheap floor-covering which did not give enough protection to my lower limbs from the intense cold rising from the floor, and in consequence I was very crabby during that winter. This in turn made me very upset for I had looked forward so much to Joe’s coming home to us again and now he was here with us I was a bag of misery at times.

Joe was having his troubles too; it was a time of great readjustment, and the real trouble lay in the fact that we were not prepared for it and were unable to cope. We had not realised that things in peace time could be just as difficult even though they were not so dangerous. We had waited so long for the men to come home from the forces and had looked forward to it as a time when our troubles would be over; things were harder than we knew.

Joe had spent the last year of his army life with the army of occupation in Germany and we had both been overjoyed when we knew that he would probably be home for the birth of the new baby. The army was pretty generous in the demob outfit given to the men on their return to civilian life and they gave Joe a sports jacket and flannels and a hat and rain coat, and his old army uniform to finish out round the garden. On the whole, apart from our separation, he had enjoyed his time in the army and it had been quite interesting once the war was over, watching at first hand how that part of Europe reacted to the peace after six years of war.

There was a great deal of hardship to be suffered by the civilian population of all the countries that had participated in the war, but since most of the fighting had taken place in France and the surrounding countries, the people there had the task of rebuilding their towns and cities and of course, vanquished Germany had the greatest rebuilding task of all for many of her capitol cities had been razed to the ground by the perpetual heavy bombing which had been the means of establishing an allied victory.

All these countries had the formidable task of forming governments that would be able to deal adequately with the transition from war to peace and to start paying for the dreadful wastage of the last six years. It involved so many things; there were the hundreds of war wounded ex-servicemen and civilians in every land to be brought back to some measure of health and usefulness again. It had always been the intention of the authorities and everyone concerned that these people who had lost their health in service to the country would have a better deal than the returned heroes of World War I. The years that followed proved that there was no special provision in society beyond the fact that each firm had to have as part of the established staff on the payroll something like 2% disabled people. In this way a few of them were absorbed into industry, but the vast majority had their mean little pension and had to manage on it as best they could.

When the men came home in England the food shortage was felt more acutely, for there was no doubt that the men in the services were much better fed than the civilian population and the men brought their huge appetites with them home to a ration book that allowed him a few ounces of meat, one ounce of bacon and one egg a week. Cheese and fat, too, were doled out in ounces and the men found it hard to believe that the small packet that came from the trip to the grocer each week had to last the household for the next seven days. It was a wearisome business trying to eke out the rations, for a man doing much more work than he had done at any time in the last eighteen months felt he was entitled to a good meal when he got home at night. What he actually got was a stew made entirely of vegetables and although most people will agree that vegetables are good and nourishing, they taste a whole lot better if they have a pound of good steak stewed along with them.

Bread was heavily rationed and the men seemed to find this a great hardship. What we had was darker in colour than that which we bought pre-war but we were thankful to have it, light or dark. There never seemed enough for sandwiches, for it was difficult, too, to find a suitable filling for them; there was very seldom anything tasty to spare and when they were made the filling was usually onions, chopped raw, or meat paste or sauce and they were very uninteresting, for they were always spread with margarine.

All the women found it difficult; it had been bad enough when there were only themselves and the children to feed, but now the men were home it was grim.

Men found their work hard and very exacting and life much more restricting than before; in the Army when their period of duty was finished they were free to go walking or to visit their friends and stroll along to the nearest N.A.A.FI, or perhaps go to one of the very good lectures arranged by the services to help the men to return to civvy street. Now at home, he had to do a full day’s work which had to be started punctually and then when the day was over and he was back at home, there were the children to be played with or perhaps punished for misdeeds committed during the day or perhaps even just to help them with their homework.

|

|

|

Coronation party 1953

The houses were in a dreadful state and ours was no exception; there were no windows in most of the rooms and there were still bits of blackout paper adorning them and now repairs were the order of the day. This would not have been too bad, but materials for repairs were expensive and in very short supply.

Most of the jobs had to be done temporarily and often with the wrong things, for instance there was no proper window glass and the kind one could get was partly opaque and one could not see out through the window even when the glass had been put in. It did let God’s light into the house once more though, and once that was accomplished the place began to look more bright and cheerful. It certainly improved the appearance of the houses once the windows were put in, for as soon as the glass was back all the women managed to beg, borrow or steal some curtains and the place began to look more homely.

Gangs of repair men were touring London doing first aid repair to the houses and gradually the ceilings were put up again in the bedrooms and they could once more be used for sleeping purposes and life began to be much more normal and orderly.

Mr and Mrs White came to live in the house next door when Mr Phillips left; for after the old lady died he was free to marry. Although he was by then about fifty years of age, he married a widow of his own age and went to live in her home.

We were very happy to have the Whites as neighbours and their son Richard was about the same age as Anne and Margaret and went to the Sacristy School with them. They played well together although sometimes one of the trio would upset the other two and the fur would fly for a while and we would hear passionate avowals that he or she would never play with the others again but the moment the next thing of interest came up they would be as thick as thieves again.

Anne made her First Holy Communion with Richard and about forty other children. We had to take them to eight o’clock Mass and they all had to assemble a quarter of an hour before time in order that the nuns could do any last minute titivating that seemed necessary.

I think everyone looked forward to First Communion days. The children had been getting prepared for months beforehand learning their catechism and we were all word perfect by the great day. We had catechism questions for breakfast, dinner and tea in the week preceding the great event and I was busy making Anne her pretty white dress and she wore my wedding veil. It was disappointing when we woke up to find that it was pouring with rain and we had a great chase round finding Wellington boots and macs for everyone. We managed to get a bus down but we were all very wet.

On these First Communion days it was the practice that the Cannon was invited to breakfast in the Convent with all the children and all the parents and other children stood around and drank cups of tea while the children ate the wonderful breakfast provided.

|

|

Holy Communion days

The heavy rain spoiled things for them a bit, for instead of being able to go out to play in the playground afterwards, they had to play in the hall and the photographs could not be taken. We managed to get a few taken later on in the day after their return home, though, as a keepsake of the day.

There was always a procession in the afternoon and we all trooped back to church at four o’clock but the procession had to be held in the church and it marred a little the pretty picture the little girls in their dresses and veils usually made as they strewed rose petals in the path of the Blessed Sacrament but still they looked very sweet with their decorated baskets strewing their flowers in the aisles of the church.

|

|

|

Holy Communion days

Margaret walked in the procession that afternoon for the first time with the other little girls behind the first communicants and the boys followed with all the other older boys as old hands.

The boys didn’t mind going to the procession if they were taking an active part but it was usually quite difficult to get them to leave their books to walk in a procession which only made them hot and tired. The rewarding factor was the party tea we always had on these occasions and which I generally left nearly ready when we set out and I only had to brew up when I came in and we could sit down and enjoy it all.

Now Anne was old enough to join the Brownies and had been looking forward for a long time for the Brown Owl to let us know that there was a vacancy for her. She went with another little girl from further up the road. June was a little older than Anne and had been a Brownie for about a year and she had the job of initiating Anne into the small tasks set for a new Brownie. After attending for a few weeks we were asked if we would buy her a uniform and we undertook to go to the guideshop in Buckingham Palace Road the very next Saturday and buy the required dress and tie and belt. Margaret was absolutely thrilled with all this and fingered all the different parts of the uniform, and one could only see that in her small mind there was a growing desire to be a fellow Brownie and have just such a uniform for herself. She was not in any way jealous of Anne but admired everything to do with this wonderful pack of little girls and when Anne came out after meeting she would go up to bed and Margaret would be waiting for her to get into bed and then Anne would tell her everything that happened at the meeting and of the things to be learned by the next meeting.

Each Brownie had to be able to catch a ball that was thrown to them six times in succession and they spent many happy hours after school trying to throw and to catch a ball. Another task to be learned was how to hop in the shape of a figure eight and the two of them would hop about until they were breathless but it was quite a few weeks before Anne could manage it without putting her other foot down. I took Margaret with me to see Anne being given the badges which enrolled her as a member of a six and she watched the proceedings very carefully and Anne became a very proud member of the Imps.

It was just over a year before Margaret was able to join and even then she was younger than the required age but Brown Owl thought she had waited long enough and Anne was very proud to take her young sister along with her and to have her to chat to on the way there and back.

|

|

|

A uniform quartet

Anne got ill with appendicitis when she was eight and we had a very anxious ten days whilst she was in hospital and for quite a long time afterwards for after making quite a quick recovery she had a relapse and had to spend a couple of weeks in bed.

The Doctor was calling to see her for a couple of days and when he thought that she was well on the way to recovery again told me to keep her in bed for another day or two and then get her up gradually but not to omit to call him if I was at all worried. He had no sooner stopped calling than poor Anne began to get very listless and did not want to eat anything. I waited for a week for an improvement but began to worry for I felt she had begun to lose ground rapidly. I sent for the Doctor and he was very concerned at her for all she was doing by this time was lying quite still in the bed with no interest in anything at all.

He gave me some tablets for her and somehow or other I misunderstood the instructions for giving them to her and gave her twice as many as I should. Joe and I spent a very worried night over her for I felt that if she lost any more strength she would be critically ill. We went to bed late after looking in at her sleeping peacefully and were astonished to be wakened soon after dawn by Anne calling loudly for the scissors and the scraps that she was cutting ready for pasting into an album before she had become ill. I hurried into my dressing gown and ran into her room and there she was, sitting up in bed, looking completely recovered and demanding something to eat as she was feeling very hungry.

I was more than happy to oblige but sure that Anne could not have regained her health and strength so quickly after being given an overdose of medicine, but when the doctor called, he advised careful nursing for the next few days and if the improvement continued to get her up gradually, but not to bother her with school for a week or two.

She was soon up and back on her feet again and back to school with the little band of smaller children she took to school with her. They always walked all the way there as Anne did not feel able to get them all on and off the bus satisfactorily but as they chatted and skipped along in a little bunch, the journey never seemed too much for them although it is about two and a half miles to St. Mary’s School. They were all given money for the bus fares but, as they walked there and back, on the way home there was always the added joy of going into the small tuck shop near the school to have a wonderful few minutes choosing the sweets they thought best value for their pennies to eat on the way home.

Anne was a great favourite with the staff at St. Mary’s for she was a good little girl and could be relied upon to look after the younger ones. She was a very hard worker, determined and an avid reader. When she was only about ten years old herself, she had a small class of children who were finding difficulty in learning to read, whom she helped in the lunch hour.

It seemed no time at all before it was Anne in the throes of scholarship preparation in the top class and doing homework every night. The boys were derisive of her efforts and teased her unmercifully. She and Margaret had a family of dolls which were looked after with great care and bathed and powdered, dressed and undressed and altogether greatly fussed over, they had a doll sized drop-side cot and the dolls were all put to bed at night and thoroughly tucked up and the cot left close beside their bed. The trick the boys used to love playing the most on the girls was a very wicked one and caused many floods of tears. They would creep out of bed early before the girls were awake and go into their bedroom to the cot and whip out a couple of the dolls and then bring them down to the kitchen, tie a string round their necks and hang them using the back of the kitchen chair as the gallows.

The girls’ wails, when they discovered the tragedy, coupled with the fiendish laughter of the boys, made a great row and took a great deal of quietening.

There were all sorts of intelligence tests in the scholarship examination homework and they were in the form of puzzles which had to be worked out on sight, and it was amazing how cute they were at solving them. The boys, in spite of all the teasing, were a tremendous help to Anne, and she got as quick as the boys at solving this type of test by working hard in order to hold her own with them and all the time and talk that was spent on these puzzles was a tremendous help to Margaret when her turn came a year or so later.