Starting a family¶

By this time I was expecting my first baby, and I had to go to some hospital to arrange for it to be born. It was quite an ordeal for me, for my own mother had had all her babies at home with the help of the district nurse and a neighbour, and she could not help me at all on how to choose a hospital.

I had a few neighbours with whom I discussed the problem and to my surprise they were unanimous that the Mother’s Hospital, belonging to and run by the Salvation Army, was the very best place to go. This completely amazed me for I did not know then that the Salvation Army cared for babies as well as bodies and souls.

I was rather shy and never having had a sister to talk such things over with, felt a little lonely on the morning I had arranged to do the booking. Anyone to whom I had spoken on the subject felt that I had left the whole thing too late and that I would have difficulty in getting things arranged. I thought this point of view ridiculous as I felt that it was my own secret shared only with my own kin until it revealed itself naturally. It proved a tiresome job waiting in a small room on hard upright chairs for my turn to see the matron. The first question she asked was “Was I married?” which made me brindle a bit, but as it was routine for her I answered her questions and was duly booked for early May. She told me that they had had a good deal of bomb damage at the hospital and I would have to be evacuated when the time came, to their war-time hospital in Derbyshire.

It seemed a long time ahead and I felt that the war would be over by then and decided not to worry about that part of the business or at least to worry as little as I could.

Ante natal examinations and preparing for the new addition to the family took up a great deal of time and the months simply flew by until the last month or two. I was very big and awkward by then and felt tired and weary and often wondered what the future held in store for us. There was a great thankfulness in my heart that the raids were now much fewer and we usually slept in our own bed.

The evacuation of mothers to be was carried out by nearly all London hospitals during the war years, to country districts where they could have their babies in more peaceful surroundings.

About thirty young mothers-to-be gathered early one morning at the entrance to the Mother’s hospital Clapton and one by one we were called inside and given a quick examination to see if we were fit for the long coach ride ahead of us. When we were all reassembled we said goodbye to the friends who had come to see us off and boarded the coach and we were off to our great adventure.

We had a couple of stops on the way for refreshment and were a tired and weary band that arrived eventually in one of the most lovely spots in the country. We were driven straight to the hospital for a check up on the way we had stood up to the journey and one or two who were overtired were kept to spend the night in the hospital and the rest of us boarded the coach again to be taken to a dispersal centre.

The evacuation officer was waiting for us at the centre and he allocated us all to various lodgings with people who had very kindly offered to take in one or more expectant mothers and there were people with cars willing to take us to our new digs.

Another girl and myself were taken to an old lady’s house and when she opened the door to us my first impression was that she was a witch. She showed us to a sitting room which was lit by a dim gas mantle and furnished with very early Victorian bric-a-brac. The bedroom which contained a very large double bed was dark and the only illumination there was a candle in a tin candle stick. I suppose the old lady was doing her best but we were both tired after the journey and dispirited and near to tears.

The old lady explained that she was too old to cater for us, but that she would help us to the best of her ability but we should have to cook for ourselves and do our own shopping. There was a fire burning in the sitting room and she had provided a loaf and two eggs and had put a kettle over the fire to boil for our tea.

We told her that we had had only a picnic lunch and had been travelling all day in the coach so she took us to the front door to point out where the shops were. They were just close by so I sallied out to find some food while the other girl lugged our suitcases upstairs and sorted things out.

I got some sausages, and the sympathetic shopkeeper let me have a small pack of margarine without coupons to help me out. I could not get any fresh milk but I managed to get a tin of Nestle’s milk and felt that I had done very well. When I got back we fried the sausages and the eggs and filled up with bread and margarine and tea. While we ate our supper we made up our minds that we couldn’t stay here and would go back to London the very next day.

We washed up and told the old lady that we were very tired and would go up to bed. She provided us with a candle and matches and we mounted the dark stairs to share a room and a bed with each other although we had only met for the first time a few short hours ago on the coach. We did not even know each other’s name.

We both had a little weep for by this time we were very lonesome, tired and very, very sorry for ourselves. After a little while we undressed and got into bed and lay talking. We found that this was a first baby for both of us and that we had both been sent by the same hospital and lived fairly close to each other in London.

We decided to leave the candle alight for company and it proved to be a very wise thing to do for after an hour or two Betty was taken ill. I had to put on my dressing gown and find out where the old lay slept in order to tell her that we needed some help. I had some coppers and she came to the front door with me and showed me where the phone box was. I went upstairs and put on a few clothes quickly and then went out to phone the hospital. Before I left the house I bade the old lady to go up to Betty who was quite sure that her baby would be born before I got back. I was frightened and wondered what on earth I should do in that dark, horrible room with only a flickering candle for light.

I only vaguely knew what the hospital was called having been there such a short time but I knew it was Willersley Castle and I sobbed out the whole story to the telephone operator. He was really kind; and helped me to pull myself together by asking questions to fill in the few details of who I was and what I wanted. I did not even know the address at which we were staying and could only describe to him where it was by what I could see from the phone box in the moonlight. He must have been a local man for he seemed to know where I was and told me to go back and keep a watch out for the ambulance.

I had never been so worried in my life before, as I was then, and I was glad to get back to Betty who was groaning softly. There didn’t seem to be any sign of the baby having arrived in my absence for which I was truly thankful but Betty seemed to be in a great deal of pain and in the state I was in I could think of no other pain in the world but labour pains which I read so much about lately.

I asked the old lady to stand at the front door until the ambulance came down the road as the driver had no address and would be expecting somebody to be on the lookout for him and show him where the patient was.

There did not seem to be anything I could do for Betty at the moment, so I re-packed the bag and her suitcase that she had unpacked a couple of hours before and then made her put on her dressing gown to be ready when the ambulance arrived. It was the work of a moment to get her and her luggage into the ambulance when it came and I watched it go off up the hill wishing with all my being that I would soon follow her.

Imagine my surprise the next morning, when I answered a knock at the door at about half past eleven, to find Betty, with her luggage standing on the doorstep. The ambulance had brought her back; it was the sausages that had upset her, not the poor baby. The hospital had only enough beds for the expected cases and the odd emergency case and as she had quickly improved once she got to the hospital, and still had about three weeks to go before she was due to be confined, they had decided that she might just as well wait her time in the company of the other expectant mothers.

I was more than gad to see her but felt sorry for her because she was so disappointed that she still had to wait for her baby. We had some tea and then decided that we would go down to visit the evacuation officer to ask if we could be boarded out somewhere where our food would be prepared for us or where there were proper facilities for us to cook our own. We were much too big at this stage to be bending over a coal fire to cook.

He was most helpful, and told us that he would have us moved by the weekend. He was as good as his word and on the following Saturday morning we joined two other members of the fat ladies club who were boarded out in a council house.

We were a bit crowded and strongly suspected that the tenant of the council house and her daughter who was about thirty years old slept down in the sitting room after we had gone to bed for they were probably glad to get the boarding fee that was paid to them by a benevolent Government for taking in evacuees. The daughter had been widowed at the evacuation of Dunkirk and had a small son of seven, a very lively little boy. The other two mothers-to-be were from London too and had been in residence for three weeks and were still waiting. The meals were wonderfully cooked and we had the added joys of a modern bathroom and electric light which we had been denied at the old lady’s house.

We all four became quite friendly and went for longish walks together but of course the hills of Derbyshire are a bit steep for people like we were. However we would walk a bit and then find one of the stone walls around that commanded a good view of one of the lovely valleys and sit there in the chilly spring sunshine and discuss the way we intended to bring up these babies when they did condescend to arrive. We felt they were tardy despite the fact that according to the reckoned dates we each of us had about a fortnight to go.

We had antenatal clinic twice a week and there was a great room put at our disposal in the hospital and the ambulance would go round the villages round about and bring all the mothers in for examination. The chatter was tremendous and the rumours that went around were many and varied.

The one that greatly upset us was that one of the mothers who had been a victim in one of the raids on London, and had the bad luck to be buried for several hours beneath piles of rubble, had been admitted to the hospital and had produced a black baby. She was stated to be of the opinion that this was due entirely to the experience she had been subjected to, as she had a white true blooded cockney for a husband and there was no other explanation that could come to mind. I suppose we were all a bit more gullible than usual for we all became afraid that our own babies would be a different colour to white and by the time I got into the examination room that day the nurse was ready for my question,”Will my baby be the right colour, nurse?”, for I had been in all the big raids on London and I told her about the rumour that was going around but she laughed and said that so long as I hadn’t spent the duration of the raids in the company of the coloured soldiers stationed in London I could be quite sure that my baby would be pink and beautiful. I felt reassured and gradually all the other girls knew what was the true cause of the black baby.

The hospital was a beautiful place and a real castle. It stood at the top of a hill and overlooked the river. It had been turned into one of the many war time emergency hospitals scattered throughout Britain in the most lovely countryside in rural England. The gardens were just at the peak of loveliness, rhododendrons and lilac and laburnum were there in all their glory, with lots of trees with their new green foliage, to rest under if the sun proved too hot. In addition to all this there were absolutely no raids at all to worry us, in fact the people in the village had never heard the siren, except on the odd occasion when it was blown off to make sure that it still worked. You can be sure that the mothers who stayed in the surrounding villages made the most of their personal bomb stories, which were more often than not grossly exaggerated and full of death and glory.

We knitted and sewed, walked and chatted the next ten days or so but during all this time I suffered a great deal of pain in my ribs. I had told the doctor at the hospital but he wasn’t very concerned and told me that it was one of the discomforts of late pregnancy and would probably go as soon as my baby was born. When we went to the clinic that week the sister in charge told me that she would like to see me in labour by the week end and gave me two two ounce bottles of castor oil with instructions to take one on Friday night and if there was no result to take the other on Sunday night.

The other girls watched me take the first bottle and laughed at my shuddering and told me that, “It was all in a good cause”, and if it had the desired effect they too would have a go. I went to bed hopefully after taking it, only to have to rise quickly a couple of hours later to be violently sick. I was very groggy for the whole of that night but when it was time to get up next morning, in spite of all the anxious inquiries about “when to call the ambulance?” and “Should they pack my bag for me?”, I had to confess that I hadn’t a pain in the world and even my rib ache had disappeared. None of the other girls could produce any pains either, so we plodded on until the next clinic when the doctor decided to keep me in hospital along with another girl, until our babies arrived.

There wasn’t long to wait, for on the Thursday night I became ill and Paul arrived at lunch time on Friday. His coming brought great rejoicing to both Joe and myself but it was the nurses that made the greatest fuss of him for he was the biggest baby that had been born in the hospital, tipping the scales at ten pounds and one ounce. The very nice young midwife who had actually delivered me carried him round in triumph and told the story of his birth to anyone who would listen.

She carried him to show the other London mothers when they came to the antenatal clinic the following week and apparently there was a great deal of chaff and fun at the cause of my rib ache that they had all heard so much about in the previous weeks.

By the time he was a week old the other girls with whom I had shared digs had had their babies too and after three weeks spent in recuperating and learning to care for our babies we were ready to go back home. We travelled home all together in the train to London and there was a bevy of new fathers to greet us at the station to take us to our own homes.

There had been two tremendous raids on London whilst we were away, two of the very worst London was to suffer and a great deal of damage had been caused, but luckily things had quietened down since and we settled down to get used to life with a young baby.

I was a little disappointed at first when I knew that a second baby was to arrive within eighteen months of Paul, but after two or three months I got the thing into proper perspective and began to look forward to it and the idea that a son and daughter would be an ideal family especially if they were close together as mine would be and I was sure that they would be the very best of friends.

|

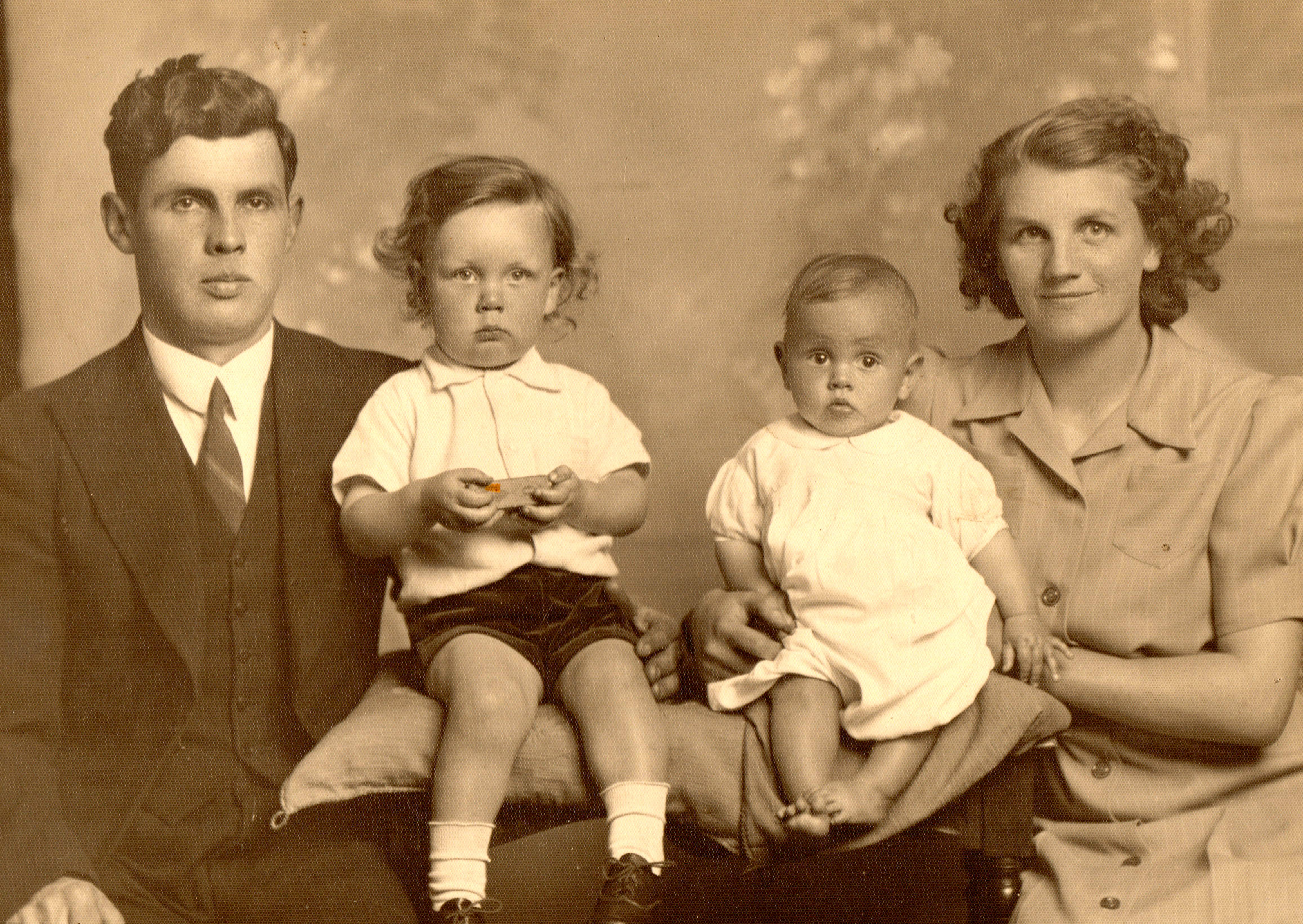

Proud parents