What if: assimilating observations that don’t yet exist¶

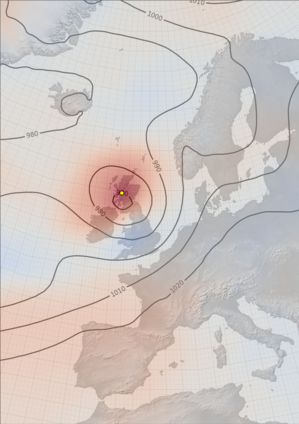

20CRv3 provides a useful, but very uncertain, reconstruction of the Christmas storm of 1811. It is uncertain mostly because it has observations from only nine European stations back in 1811.

There were many more than nine European locations making barometric pressure observations, even in 1811. The Copernicus Climate Change Service Data Rescue Service have found records from 43 additional locations containing barometer observations. We’d like to rescue, and assimilate, the observations from these locations, but data rescue is time consuming and expensive, it would be useful to demonstrate the value of this work, before doing it - how much of an improvement would we expect, if we did the data rescue.

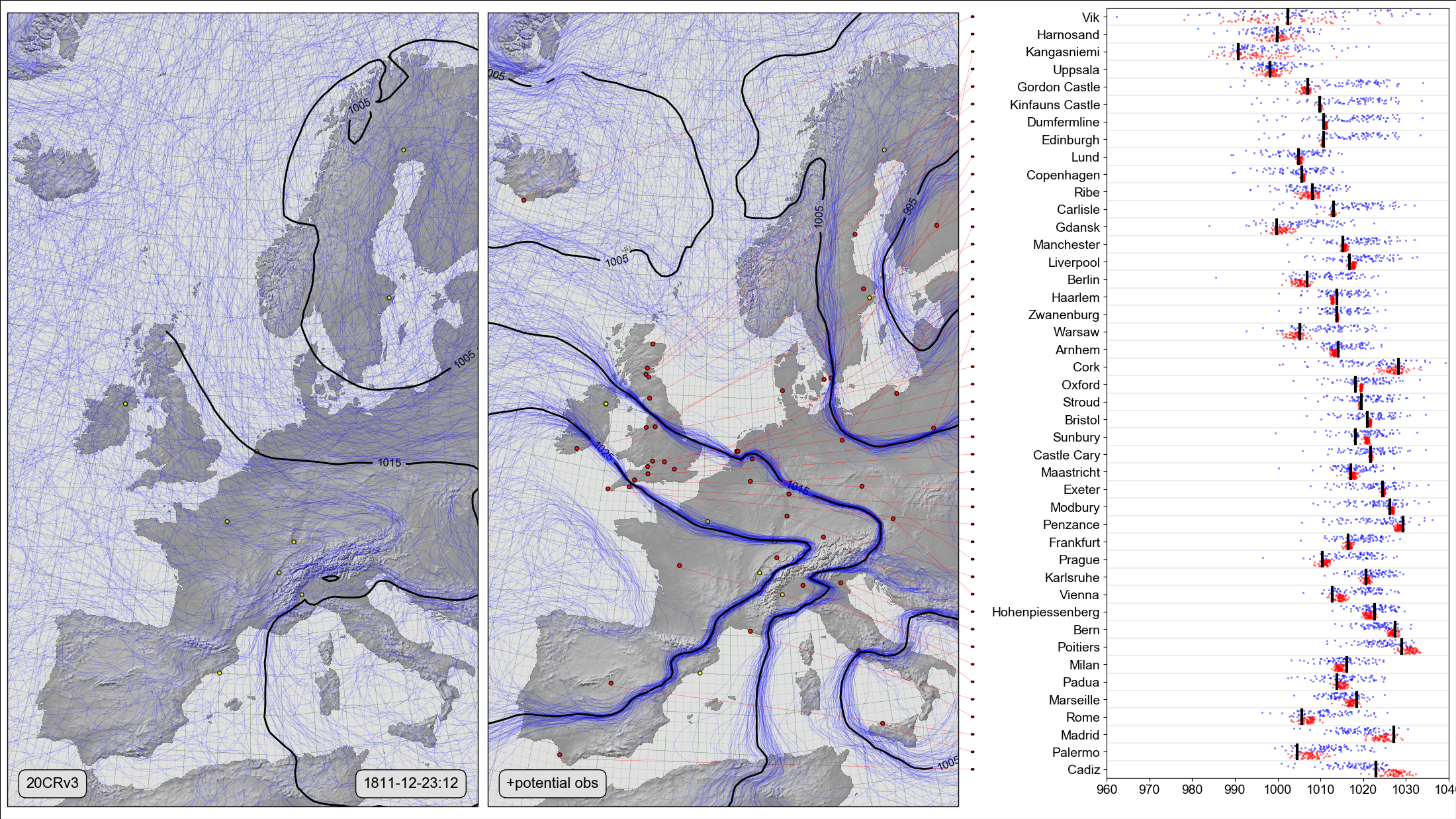

To demonstrate this, we can generate some plausible, but fake, observations from the potential locations, and assimilate those instead:

On the left, a Spaghetti-contour plot of 20CRv3 MSLP at noon on December 23rd 1811. Centre and right, Scatter-contour plot comparing the same field, after assimilating 44 fake observations at that date. The centre panel shows the 20CRv3 ensemble after assimilating all 44 fake observations (red dots). The right panel compares the two ensembles with the new observations: Black lines show the observed pressures, blue dots the original 20CRv3 ensemble at the station locations, and red dots the 20CR ensemble after assimilating all the observations except the observation at that location. (Figure source).¶

To make the fake observations, we took the mslp from ensemble member 1 of 20CRv3 at the location of each station, at the time of the field, and added a bit of noise. Because the fake observations were all taken from the same ensemble member, they are mutually consistent, and can be collectively assimilated. But the resulting post-assimilation ensemble will be clustered around the ensemble member used, rather than the (unknown) real weather. This weather map should give a reasonable estimate of the quality of reconstruction we could get if observations were rescued for all the potential stations, but it’s not an accurate map of the actual weather at the time.

If we did the data rescue, our reconstructions of the weather of the early nineteenth century would improve dramatically. Comparing this map with the effects of the Daily Weather Report stations (nearly a century later) shows that the 1811 ensemble of opportunity does not produce as good results as the carefully-sited DWR stations, but the observations are well worth rescuing even so.